i've been working on a toy inference engine for the past little while that basically helps to visualize how kvcache works.when i started to get into mlsys i wanted to study the systems stuff specifically, how the kv cache works, how we store it on a gpu, and how different scheduling policies hurt (or save) latency, this was my solution to this.

i built two main binaries for this: a c++/cuda synthetic engine, and a token-time simulator. i've written below a lot of what i learned from it:

note: just fyi, since this was mostly for understanding the overarching concepts, i've made deliberate simplifications (like processing K/V on cpu and transferring to gpu, using fp32 instead of fp16, using O(n) lru operations, etc).

kv cache: why we need it and what it costs

when an llm generates tokens, it doesn't re-compute the attention for every previous token in the history every single step, as this would be very slow. instead, we store the key (k) and value (v) vectors for previous tokens in a cache.

in a transformer, attention at layer l for generating token t needs to look at all previous tokens 0...t-1. without a kv cache, you'd compute:

for each new token t:

for each layer l:

for each previous token i in [0, t-1]:

compute key[i] = W_k @ x[i]

compute value[i] = W_v @ x[i]

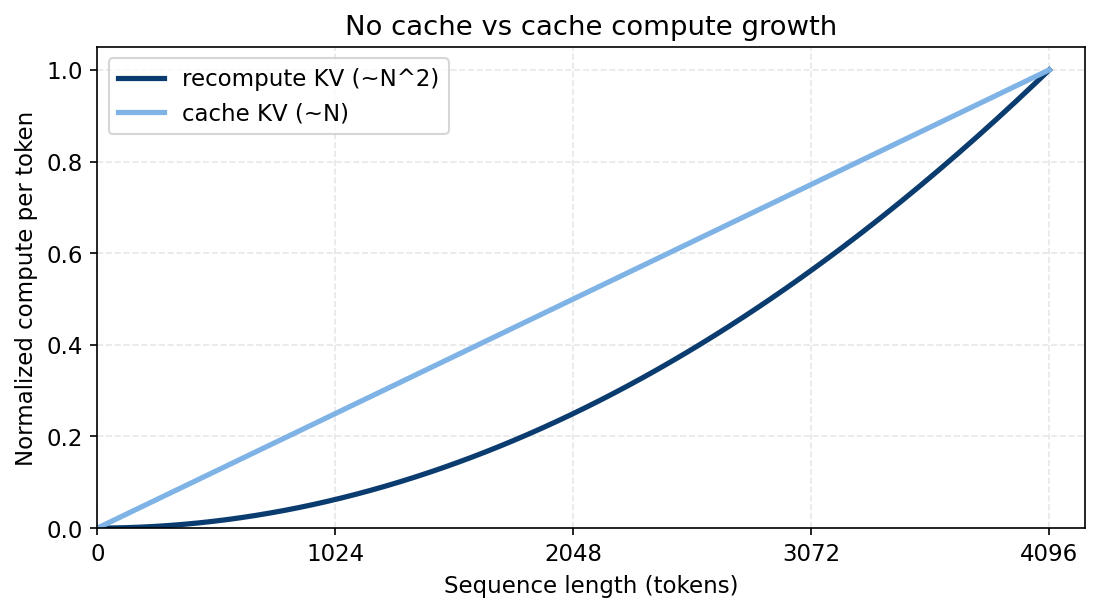

compute attention using all keys and valuesthe main issue here is that you're recomputing W_k @ x[i] and W_v @ x[i] for every previous token every time you generate a new token. for a 1000-token prompt, the 1001st token would recompute 1000 key-value pairs. the 1002nd would compute 1001 pairs. we observe that this is obviously very ineficient, and scales as O(n²) in compute.

the kv cache solves this by storing those intermediate results:

# prefill phase (process entire prompt once)

for each token i in prompt:

for each layer l:

k[l][i] = W_k @ x[i]

v[l][i] = W_v @ x[i]

store k[l][i] and v[l][i] in cache# decode phase (generate one token at a time)

for each new token t:

for each layer l:

k[l][t] = W_k @ x[t] # only compute for NEW token

v[l][t] = W_v @ x[t]

store k[l][t] and v[l][t] in cache

compute attention using cached k[l][0:t] and v[l][0:t]

now we're O(n) per token instead of O(n²), but at the cost of memory.

where does your vram go?

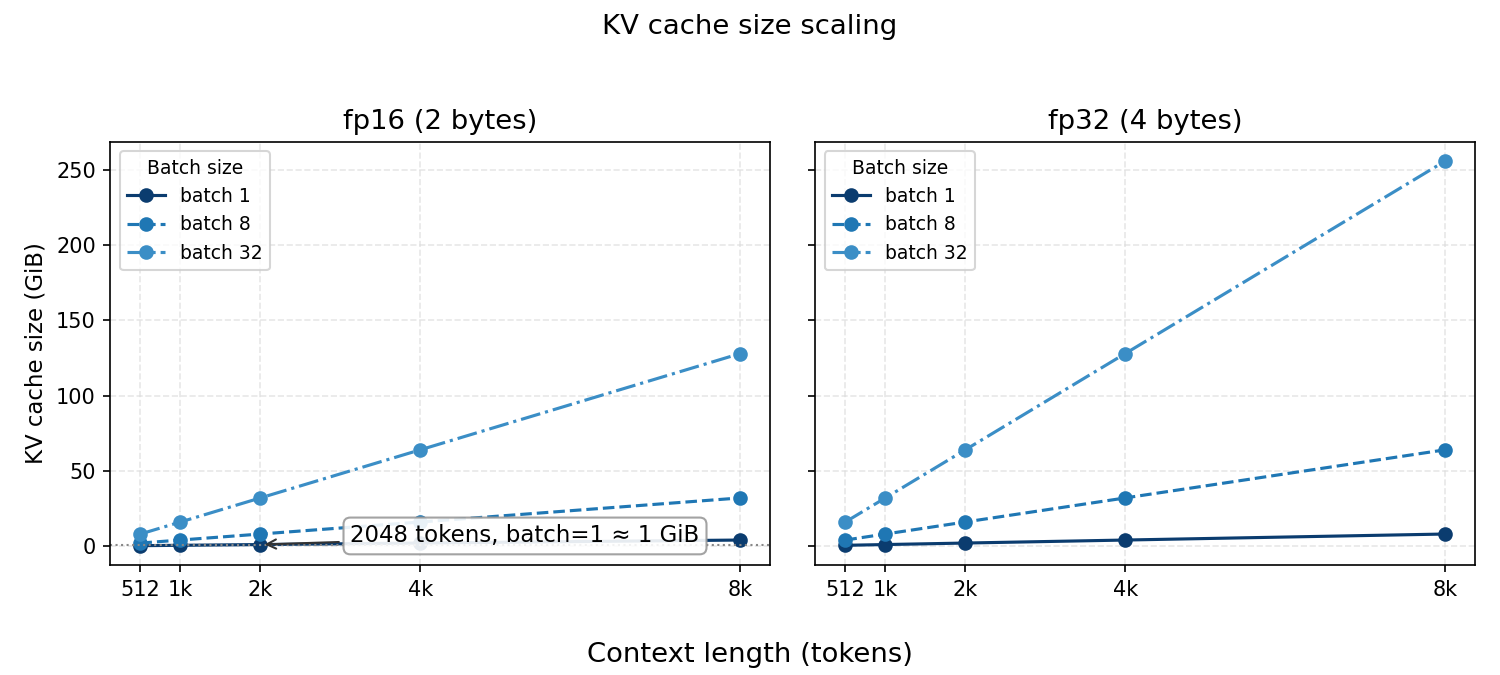

say you're running llama-7b (32 layers, 32 attention heads, 4096 hidden dimension, head dimension of 128). you want to generate a response to a 2048-token prompt.

first, we'd calculate the kv cache size for a single sequence at a single layer. as detailed in this great breakdown of transformer inference arithmetic, each token needs to store:

- one key vector:

hidden_dimfloats - one value vector:

hidden_dimfloats

2 hidden_dim sizeof(element) bytes.for llama-7b with fp16 (2 bytes per element):

per token per layer = 2 * 4096 * 2 bytes = 16,384 bytes = 16 KBacross all 32 layers:

per token all layers = 16 KB * 32 = 512 KB per tokenfor a 2048-token context:

total kv cache = 512 KiB * 2048 = 1,048,576 KiB = 1 GiBone sequence with a 2048-token context uses 1 gib of vram just for the kv cache. this is separate from the model weights (which are ~13 gib for llama-7b in fp16) and the activations needed during forward passes. as you can guess, this uses a lot of memory!

note: as i mentioned earlier my implementation uses fp32 (4 bytes) everywhere for simplicity. this means my memory footprint is 2x larger than it should be, but it made the cuda code easier to write.

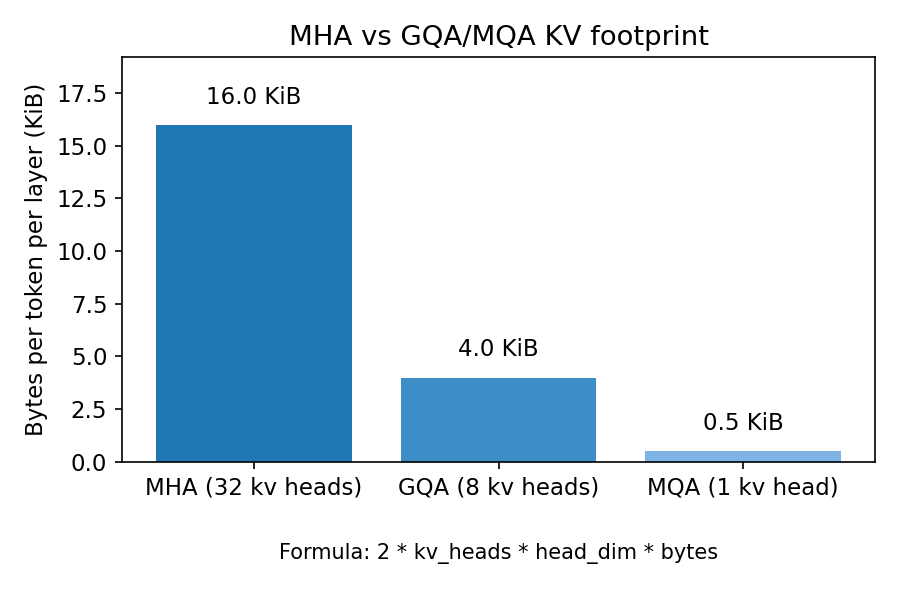

also, for standard multi-head attention (mha), each token stores keys and values with hidden_dim elements. for grouped-query attention (gqa) or multi-query attention (mqa), the kv width scales with kv_heads * head_dim instead, which can be much smaller (e.g., 8 kv heads vs 32 query heads). this reduces cache bytes proportionally, which is why gqa/mqa are so effective for long-context serving.

two kinds of caching

there are actually two different "caches" people talk about in llm serving, each working differently:

1. per-request kv cache:

this cache stores the k/v vectors for tokens within a single active request, and only lives for the duration of that request's generation. during decode, you would append one newtoken's k/v per step.

generally you can't evict tokens from an active request without breaking attention (as the model expects to see all previous context), however there are some exceptions (such as sliding window attention, where you explicitly discard old tokens and accept degraded long range attention).

2. prefix cache / cross-request kv reuse:

stores k/v for common prompt prefixes that multiple requests share. for example, a system prompt "you are a helpful assistant" may appear in 80% of requests. prefix caching uses reference counting, where multiple active requests can point to the same cached prefix blocks.

my implementation conflates these two a bit, so i apologize for any confusion.

blocked storage

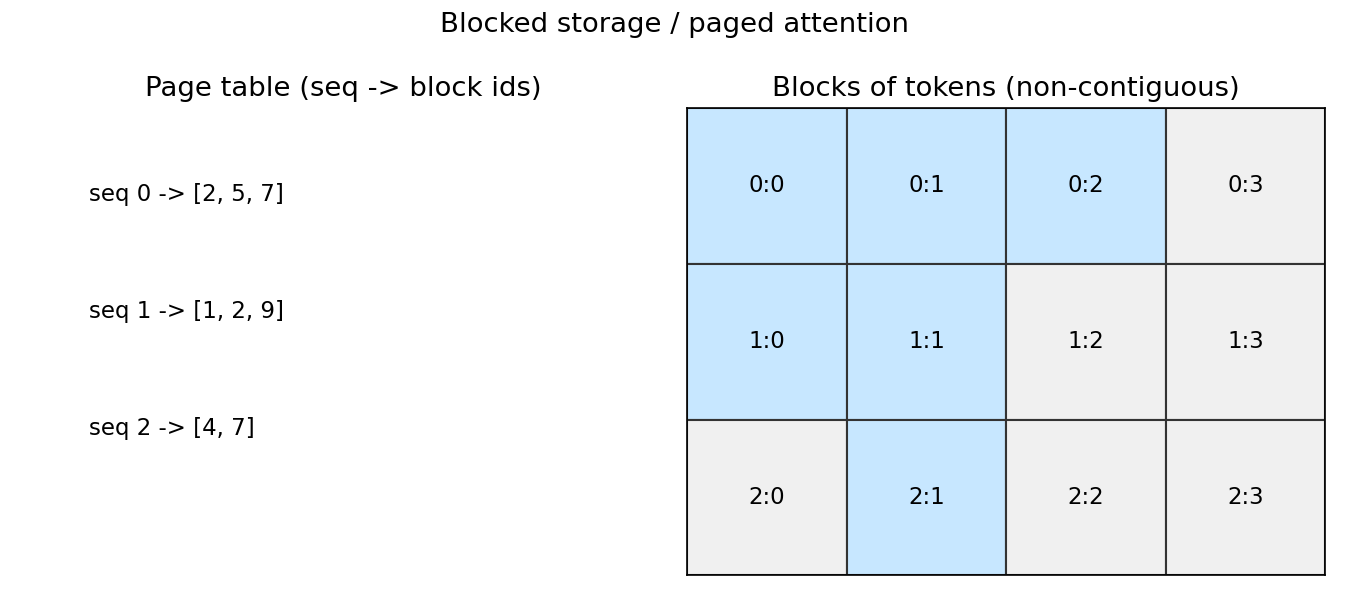

instead of allocating a massive chunk per sequence, i went with fixed-size blocks. this is inspired by vllm's pagedattention (kwon et al., 2023).

in my implementation, each block stores block_size tokens worth of kv data:

cpp

size_t bytes_per_block = block_size * hidden_dim * 2 * sizeof(float);for block_size = 16 and hidden_dim = 4096 in my fp32:

bytes_per_block = 16 * 4096 * 2 * 4 = 524,288 bytes = 512 KiBin an fp16 system, this would be half: 256 KiB per block per layer.

notice this is per layer. so a single block across all 32 layers of llama-7b would actually be 512 KiB * 32 = 16 MiB (in fp32) or 8 MiB (in fp16).

i choose to use blocks, because this allows us to allocate memory in fixed chunks, enabling easier memory management. it also allows for sharing of blocks between sequences with common prefixes (prefix cache).

in allocate_block(), when i run out of free blocks, i need to evict something:

cpp

BlockID KVCache::allocate_block(SequenceID seq_id) {

BlockID block_id;

if (!free_blocks_.empty()) {

block_id = free_blocks_.back();

free_blocks_.pop_back();

log_event("ALLOC", block_id, seq_id);

} else {

// eviction logic based on policy

block_id = evict_victim();

log_event("EVICT", block_id, seq_id);

}

// reset scores for reuse

block_frequency_[block_id] = 0.0f;

block_value_[block_id] = 0.0f;

return block_id;

}note: in my implementation, i treat eviction as if we can just kick out any block. in reality, for the per-request cache, you can't evict blocks from an active sequence without recomputation. the eviction logic makes more sense for the prefix cache layer, where you're choosing which shared prefixes to keep across requests.

eviction policies

once you've burned through max_blocks, every new block needs to kick out an old one. the policy you choose will change the behavior of a system.

lru

least recently used is straightforward. i maintain lru_list_, a deque tracking block access order. every time touch_block() is called (when a block is read during attention), i move it to the front:

cpp

void KVCache::touch_block(BlockID block_id) {

if (policy_ == EvictionPolicy::LRU) {

// remove from current position

lru_list_.erase(

std::remove(lru_list_.begin(), lru_list_.end(), block_id),

lru_list_.end()

);

// move to front (most recent)

lru_list_.push_front(block_id);

}

// update decay-based scores...

}note: this erase(std::remove(...)) pattern is O(n) per touch, which is terrible for performance. i did it this way because it's simple to understand. you'd standardly would use an intrusive linked list or a hash map + doubly-linked list (like in red is) to get O(1) operations.

when evicting, i grab the back of the deque (least recently used):

cpp

BlockID victim = lru_list_.back();

lru_list_.pop_back();lru is great when you have repeated queries with the same prefix, however it fails with sequential access patterns. if you're processing unique long documents that don't fit in cache, every new block evicts an old one, and you get 0% hit rate.

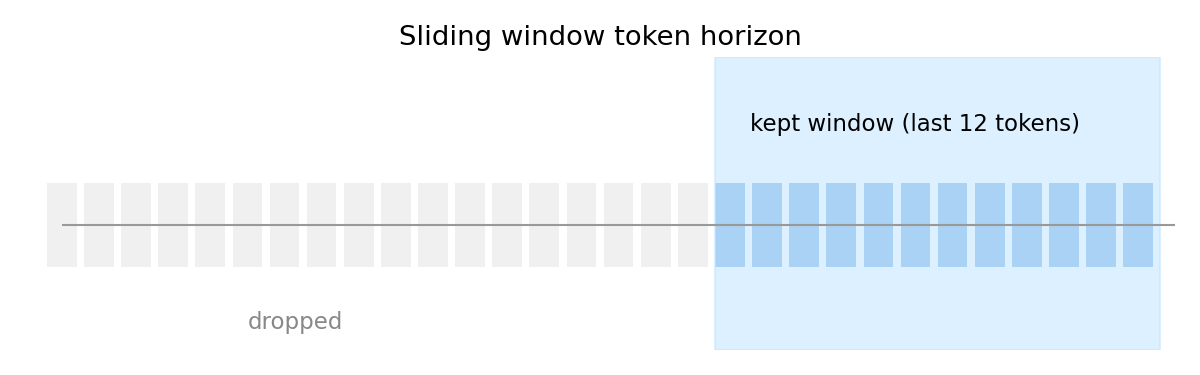

sliding window

sliding window works simply by only keeping the last window_size tokens per sequence.

in store_token(), after placing the new token, i check if the sequence has exceeded its window:

cpp

void KVCache::store_token(SequenceID seq_id, const float* key, const float* value) {

// ... place token in block ...

if (window_size_ > 0) {

auto& seq_tokens = seq_tokens_[seq_id];

while (seq_tokens.size() > window_size_) {

TokenID old_token = seq_tokens.front();

seq_tokens.pop_front();

// evict the block containing old_token

// (simplified; actual code handles block ref counting)

}

}

}this gives predictable memory usage which can be calculated with: sequences window_size bytes_per_token.

despite the benefits, you lose long-range attention. models like llama with 4096-token context windows get crippled if you set window_size = 1024. in a case like this, the model literally can't "see" tokens beyond that horizon.

lfu with exponential decay

lru and sliding window are recency-based. in certain cases though, we want to treat some blocks as more "important" than others.

i implemented a decay-based lfu where each block tracks a score that increases on access but decays over time:

cpp

void KVCache::touch_block(BlockID block_id) {

// ... lru list updates ...

if (policy_ == EvictionPolicy::LFU || policy_ == EvictionPolicy::COST) {

block_frequency_[block_id] = block_frequency_[block_id] * frequency_decay_ + 1.0f;

block_value_[block_id] = block_value_[block_id] * value_decay_ + 1.0f;

}

}the decay formula score = score * decay + 1 is interesting. with decay = 0.9:

- first access:

score = 0 0.9 + 1 = 1.0 - second access:

score = 1.0 0.9 + 1 = 1.9 - third access:

score = 1.9 0.9 + 1 = 2.71 - if not accessed for 10 steps:

score = 2.71 0.9^10 ≈ 0.94

moving data

typically, during inference, k/v vectors are computed on the gpu from gpu activations (via matmuls W_k @ x and W_v @ x), so they never touch the cpu. my implementation does cpu-side generation followed by H2D transfer because it made the synthetic transformer simpler to write. this was nice for understanding memory movement, but it's not quite representative of what you'd usually see

the layout

on the gpu, i allocate two massive flat buffers:

cpp

struct DeviceKVLayout {

float* d_keys; // [max_blocks * block_size * hidden_dim]

float* d_values; // [max_blocks * block_size * hidden_dim]

float* d_staging; // [batch_size * 2 * hidden_dim]

cudaStream_t stream;

};when a token at position slot in block block_id needs to be stored, the address is:

cpp

size_t key_offset = (block_id * block_size + slot) * hidden_dim;

size_t value_offset = key_offset; // same indexing for valuesunlike a naive approach, we're randomly scattering data into blocks. this means non-contiguous memory access, which can hurt cache locality on the gpu.

the three-stage pipeline

this is how i implemented it:

stage 1: host staging

in KVCache::store_token(), i pack the key and value into a host-side staging buffer:

cpp

void KVCache::store_token(SequenceID seq_id, const float* key, const float* value) {

// ... find block and slot ...

// pack into staging buffer

std::memcpy(staging_buffer_.data(), key, hidden_dim_ * sizeof(float));

std::memcpy(staging_buffer_.data() + hidden_dim_, value, hidden_dim_ * sizeof(float));

// ...

}this gives us a contiguous chunk: [key[0]...key[hidden_dim-1], value[0]...value[hidden_dim-1]].

stage 2: async h2d transfer

then i launch an async copy to the gpu staging buffer:

cpp

void DeviceKVLayout::stage_block(const float* h_kv_data, size_t token_count) {

size_t bytes = token_count * 2 * hidden_dim * sizeof(float);

cudaMemcpyAsync(d_staging, h_kv_data, bytes,

cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, stream);

}we need Async here so that it doesn't block the cpu thread. we can queue up more work while the transfer happens.

stage 3: scatter kernel

finally, a custom kernel moves data from the staging buffer to the final location:

cpp

__global__ void move_block_kernel(

float* d_keys, float* d_values,

const float* d_staging,

BlockID block_id, size_t slot,

size_t block_size, size_t hidden_dim

) {

size_t idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

size_t total = 2 * hidden_dim; // key + value

if (idx < total) {

size_t base_offset = (block_id * block_size + slot) * hidden_dim;

if (idx < hidden_dim) {

// copy key

d_keys[base_offset + idx] = d_staging[idx];

} else {

// copy value

size_t value_idx = idx - hidden_dim;

d_values[base_offset + value_idx] = d_staging[idx];

}

}

}this kernel is launched with a 1d grid over 2 * hidden_dim elements. each thread copies one float from staging to its final home.

what matters in decode?

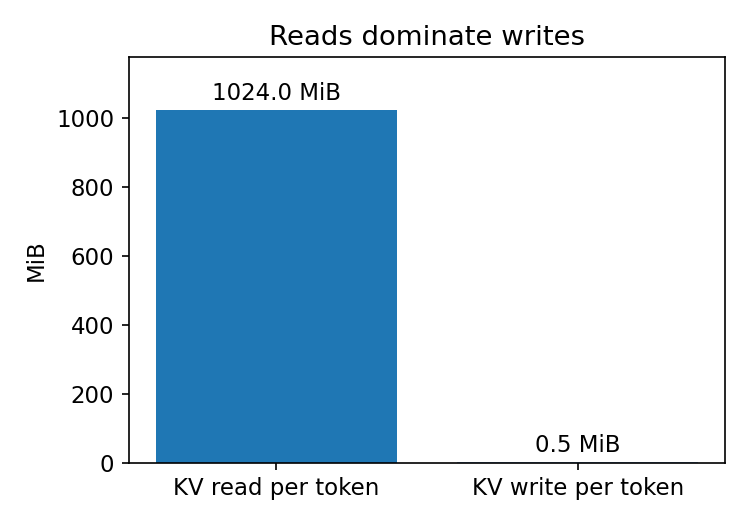

during the decode phase, the bottleneck isn't writing one new token's k/v per step, as that's only tens of KB. rather, it's reading the entire kv cache for all previous tokens to compute attention for every layer that results in long throughput.

let's recalculate for llama-7b with a 2048-token context, using fp16:

per decode step, per layer:

read all keys: 2048 tokens * 4096 dim * 2 bytes = 16 MiB

read all values: 2048 tokens * 4096 dim * 2 bytes = 16 MiB

total read: 32 MiB per layeracross 32 layers:

total read per token: 32 MiB * 32 layers = 1024 MiB = 1 GiBplus you write the new token's k/v:

write: 2 * 4096 * 2 bytes * 32 layers ≈ 0.5 MiBso generating one token with a 2048-token context requires reading ~1 gib from vram. on a gpu with ~1-2 TiB/s of hbm bandwidth (eg. a100), this gives a theoretical bandwidth ceiling of:

1.5 TiB/s / 1 GiB per token ≈ 1,500 tokens/s (bandwidth ceiling)though this is just the bandwidth ceiling for reading the kv cache. actual decode throughput is much lower because attention also does QK^T matmuls and softmax operations, adding compute overhead, and memory access patterns will never be perfectly sequential.

in practice, you get maybe 100-200 tokens/s per sequence depending on batch size, implementation quality, and context length. the key takeaway to note is that decode is fundamentally memory-bandwidth-bound by reading the kv cache for attention, not by writing new tokens.

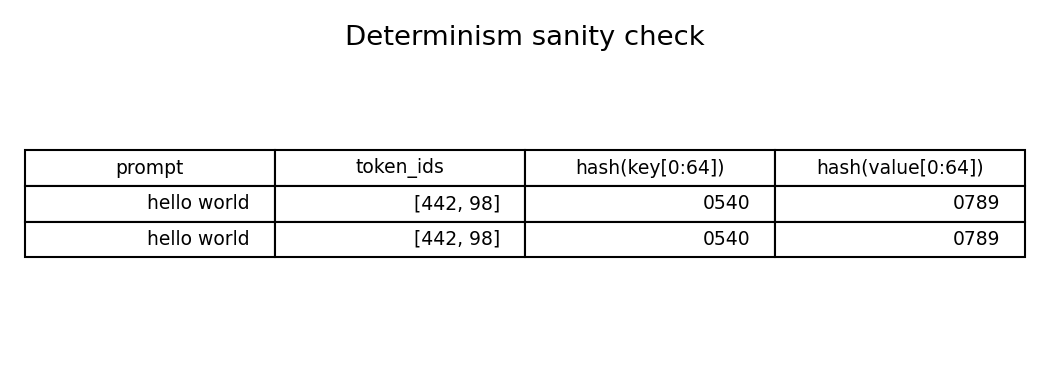

deterministic key-value generation

i didn't want to deal with loading real model weights, so i built a fake transformer that produces deterministic k/v vectors.

in src/transformer.cpp:

cpp

void TransformerBlock::forward(TokenID token_id, size_t step,

float* key_out, float* value_out) {

float base = (token_id % vocab_size_) / static_cast<float>(vocab_size_);

for (size_t i = 0; i < hidden_dim_; ++i) {

key_out[i] = std::sin(base + 0.01f * step + 0.001f * i);

value_out[i] = std::cos(base + 0.01f * 1.3f * step + 0.001f * 1.3f * i);

}

}this is just sin and cos with some offsets. the token id shifts the base frequency, the step adds a temporal component (like positional encoding) and the dimension index adds variation across the vector.

this works because i don't actually care about the values of the keys and values. i only care that the vectors are realistically sized, and produce different k/v for different tokens (while still being deterministic)

i hash prompts into token ids:

cpp

std::hash<std::string> hasher;

for (const auto& word : prompt_words) {

TokenID token_id = static_cast<TokenID>(hasher(word) % vocab_size);

token_ids.push_back(token_id);

}so if i pass --prompt "hello world", it becomes two deterministic token ids. this let me test the cache with real-ish sequences without needing a tokenizer.

queueing theory

src/sim_main.cpp

as stated, llm inference has two distinct phases, they can be summarzed as follows:

prefill (prompt processing):

- processes all prompt tokens in parallel

- high throughput

- bottlenecked by memory bandwidth and matmul compute

- processes one token at a time per sequence

- low throughput

- bottlenecked by memory bandwidth (reading kv cache for attention)

cpp

struct ServerParams {

float tokens_per_ms_prefill; // e.g., 10.0 (10k tok/s)

float tokens_per_ms_decode; // e.g., 0.1 (100 tok/s)

size_t max_batch; // how many requests can process concurrently

};the event loop

the simulator maintains an event priority queue:

cpp

struct Event {

float time_ms;

EventType type; // ARRIVAL, PREFILL_DONE, DECODE_CHUNK_DONE, etc.

RequestID request_id;

};std::priority_queue<Event> event_queue;

the main loop processes events chronologically:

cpp

while (!event_queue.empty()) {

Event evt = event_queue.top();

event_queue.pop();

current_time = evt.time_ms;

switch (evt.type) {

case ARRIVAL:

handle_arrival(evt.request_id);

break;

case PREFILL_DONE:

handle_prefill_done(evt.request_id);

break;

case DECODE_CHUNK_DONE:

handle_decode_chunk(evt.request_id);

break;

}

}when a request arrives, it enters the prefill queue. when prefill completes, it moves to the decode queue. when decode finishes all tokens, the request is complete.

scheduling

ml systems like vllm and sglang are able to differentiate themselves in terms of performance by effectively choosing which requests to process next when the server becomes idle.

fcfs (first-come, first-serve):

cpp

RequestID schedule_fcfs(const std::deque<RequestID>& queue) {

return queue.front(); // trivial: just pick the oldest

}fcfs is fair a fair way to schedule, but terrible for latency. imagine three requests arrive:

1. request a: 2000-token prefill, 500-token decode

2. request b: 10-token prefill, 10-token decode

3. request c: 50-token prefill, 50-token decode

with fcfs, request b waits behind request a's massive prefill, even though b could finish in milliseconds.

srpt (shortest remaining processing time):

cpp

RequestID schedule_srpt(const std::vector<Request>& requests) {

return *std::min_element(requests.begin(), requests.end(),

[](const Request& a, const Request& b) {

size_t remaining_a = a.num_output_tokens - a.generated_tokens;

size_t remaining_b = b.num_output_tokens - b.generated_tokens;

return remaining_a < remaining_b;

});

}srpt is provably optimal for minimizing average completion time in non-preemptive queues. it drastically reduces tail latency because short requests zip through, but it can be considered unfair as long requests can get starved if short requests keep arriving.

slo-aware scheduling:

cpp

RequestID schedule_slo(const std::vector<Request>& requests, float current_time) {

return *std::min_element(requests.begin(), requests.end(),

[current_time](const Request& a, const Request& b) {

float slack_a = a.slo_ms - (current_time - a.arrival_time);

float slack_b = b.slo_ms - (current_time - b.arrival_time);

return slack_a < slack_b; // prioritize smallest slack

});

}if each request has a deadline (slo), we prioritize the one with the least time remaining until deadline.

in practice for this to work you need a good estimate of how long a request will take. if your estimate is wrong, you'll miss deadlines, however if you're correct, it's great for workloads where some users pay for guaranteed latency.

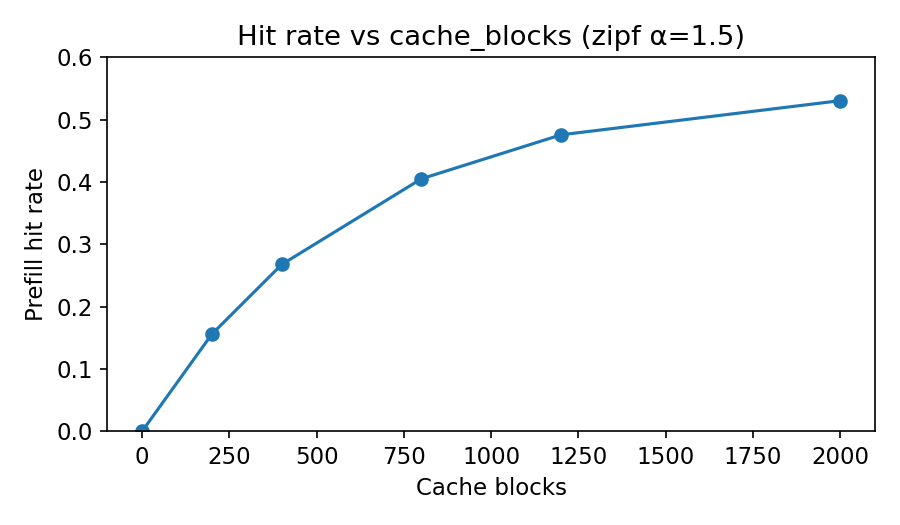

prefix cache

my repo also includes a simple prefix cache model (src/simulator.cpp, PrefixCacheModel):

cpp

struct PrefixCacheModel {

std::unordered_map<PrefixID, CachedPrefix> cache_;

size_t capacity_blocks_;

EvictionPolicy policy_;

size_t check_hit(PrefixID prefix_id, size_t prompt_tokens);

void update(PrefixID prefix_id, size_t prompt_tokens);

};this is modeling the cross-request prefix cache, not the per-request kv cache. when a request arrives, i hash its prefix and check if it's cached:

cpp

size_t hit_tokens = prefix_cache.check_hit(request.prefix_id, request.prompt_tokens);

size_t effective_prompt_tokens = request.prompt_tokens - hit_tokens;the prefill work is reduced by the hit tokens. this results in speedup from reusing cached k/v across requests.

i round prefixes to block boundaries to match the block-based cache:

cpp

size_t prefix_blocks = (prompt_tokens + block_size - 1) / block_size;so a 50-token prefix with block_size = 16 uses ceil(50/16) = 4 blocks = 64 tokens of capacity.

tracking prefill_hit_rate across runs showed the impact of cache capacity. with capacity_blocks = 0 (no cache), hit rate was obviously 0%. with capacity_blocks = 1000 and zipfian traffic (α = 1.5, very skewed), hit rate reached 40-50%, because the popular prefixes fit in cache.

this is why systems like vllm push so hard on prefix sharing. if 80% of requests share the first 500 tokens, caching those saves 80% * 500 tokens of prefill work on every request.

tldr

building something helps you learn a concept better. would highly recommend. writing about this helped build my intuition about kv cache far better. however, it also taught me that i should probably build stuff knowing that it'll be seen and that i'll need to explain it. the repo for this project was kinda a mess that only i could understand, so writing this out was actually a bit tough.

---

references:

- transformer inference arithmetic by kipply - excellent breakdown of memory costs and bandwidth limits in llm inference

- kwon et al., "efficient memory management for large language model serving with pagedattention," 2023 (arxiv) - the vllm paper that inspired the block-based cache design